Puccini A to Z – F as in La Fanciulla del West

F as in La Fanciulla del West

La Fanciulla del West is one of Puccini’s last operas: the premiere took place on December 10, 1910 at the Metropolitan Opera Theater in New York, with Toscanini on the podium and Caruso on stage.

Back in 1907, Puccini had seen, in New York, a drama by David Belasco, “The Girl of the Golden West”. Moved by the story, he shortly obtained the rights from its author to make an opera out of it and asked poet Carlo Zangarini to write the libretto. Zangarini was later helped by Guelfo Civinini.

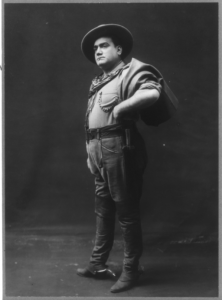

Enrico Caruso in La Fanciulla del West – March 4, 1911

Puccini began working on the music in the summer of 1908, but the work was to be completed only two years later. Puccini was under a lot of stress for more than one reason: his close friend and librettist Giuseppe Giacosa, who had worked along with Luigi Illica on the libretti of La Bohème, Tosca and Madama Butterfly, had died in 1906; Puccini was famous, but that came with the price of always being up to par, and the pressure of producing a new masterpiece was daunting; but the biggest sorrows came from his private life.

A family matter

A young servant, Doria Manfredi, had been employed at Puccini’s house for a few years; in 1908 Puccini spent the summer in Cairo and when he came back to Torre del Lago, his wife Elvira became unexpectedly jealous of Doria. Elvira accused the woman of having a relationship with her husband and fired her. In a small and gossipy town as Torre del Lago, Doria cracked under the pressure of being seen everywhere as a gold digger eventually poisoning herself to death. It was one of the biggest scandals of those years: Doria’s parents ordered the body to be examined by a physician who declared the girl was still a virgin.

The Manfredis sued the Elvira for persecution and calumny. Puccini paid damages to the Manfredis who withdrew their accusations, Elvira was found guilty but not sentenced. The whole episode left a deep scar in Puccini’s marriage and threw him in a depression that prevented him from continuing his work on La Fanciulla del West. He himself admitted it in a letter to his friend Sybil Seligman: “La mia vita passa in mezzo alla tristezza e alla più grande infelicità […] Come risultato La Fanciulla si è completamente inaridita – e Dio solo sa quando avrò il coraggio di riprendere il lavoro”. (My life is going through sadness and great unhappiness […] As a result Fanciulla dried out and God only knows where I’ll have the courage to start working again).

Act 1

The first act opens in the “Polka”, the saloon managed by a peculiar and strong girl, Minnie. The men play cards, thinking about their families and hoping for a better life. Minnie enters and starts reading the bible to the miners, trying to teach them something. Rance, the feared and respected local sheriff, declares his love for Minnie, who replies in an elusive way.

Dick Johnson, a stranger, comes in. Minnie knows him as the man she bumped into once on the way to Monterey and that she immediately had fallen for. But the man is, in fact, the bandit Ramerrez, come only to steal the miners’ savings. Captured by the Minnie’s charm, he gives up on his plan almost immediately. While the two are dancing, the miners leave the saloon to chase the group of Mexican bandits who came with Ramerrez. Johnson-Ramerrez and Minnie, left alone, confide in each other and eventually the girl invites him to her room.

Act 2

The second act takes place in Minnie’s dwelling. After a brief conversation with two native Americans who live with her, Johnson finally arrives. The engaging love duet between him and Minnie is interrupted by the arrival of Rance and the other boys, who warn Minnie that the Johnson is no other than the bandit Ramerrez. Minnie, outraged, chases out the man, who, shortly after, gets shot, comes back in and collapses. Minnie helps him by hiding him in the hut. The sheriff is back, looking for Johnson in every corner without finding him; then, a drop of blood falling from the ceiling reveals his presence. Minnie then advances a desperate proposal: poker game; if Rance wins it, he will have the woman and the bandit’s life. But Minnie cheats, saving herself and her man.

Act 3

Johnson is again on the run, chased by the miners who soon manage to capture him. They all want to hang him and Johnson accepts the verdict, only asking that they save Minnie from the pain of his death. Here Johnson sings the famous aria “Ch’ella mi creda libero e lontano” (“That she believes me free and far away”). But Minnie arrives, throws herself in front of Johnson and begs the miners to save his life. She remembers the teachings of the Bible, talking to them one by one. Moved by her words, the miners agree to set him free. Minnie and Johnson leave together to start a new life.

La Fanciulla del West – Recordings

The number of recordings of Fanciulla is, as it might be expected, quite extensive. Starting with the 1950 recording by the

La Fanciulla del West – film poster by Spellani

Orchestra RAI of Milano with Arturo Basile conducting Carla Gavazzi as Minnie and Vasco Campagnano as Johnson, the main roles were taken on by major voices in the opera world: Maria Caniglia and Giacomo Lauri-Volpi, Eleanor Steber and Mario del Monaco, Gigliola Frazzoni, Franco Corelli and Tito Gobbi at La Scala in 1956 conducted by the great Antonino Votto, Magda Olivero and Giacomo Lauri-Volpi, getting all the way to the present days with one Eva-Maria Westbroek depicting one of the greatest Minnies.

For a list of recordings you can consult this page.

The opera was also portrayed in several movies: the first time in a 1915 film by Cecil B. DeMille, and then by Edwin Carewe in 1923 and John Francis Dillon in 1930 (though the latter was lost).

A turning point?

La fanciulla del West is often considered the turning point in Puccini’s composition style. In fact, the change had already began with Madama Butterfly. However, Fanciulla jumps forward in the core thematic idea of the opera: we are used to the fate of Puccini’s characters whose destiny is, one way or another, doomed. Fanciulla shows a different approach to it, the underline theme of the whole opera being redemption. Everything depends on it, everything is built on it in order to have a happy ending.

This one aspect brought Puccini more than one criticism (though we know that Puccini’s detractors were and are far from being impartial). To top this off, he was also accused of stealing from other composers, especially Debussy. Truth is that like any great composer Puccini was extremely conscious of the musical world around him. His constant quest for something new brought him to explore different worlds and include them into his own personal language. Some of Debussy’s peculiarities had already been used in Tosca or Butterfly; the increasing importance of the orchestra in Fanciulla and the finesse in the orchestration is nothing but a natural evolution of a great composer.

The orchestra

The orchestration makes also use of peculiar instruments or of “prepared” instruments: for instance, in the first act Wallace’s song is accompanied by two harps, one in the orchestra and one off stage with paper between the strings in order to imitate the banjo; the end of the act uses an instrument especially built by Romeo Orsi consisting of a series of metal plates placed in a harmonic box that produce a particular kind of vibrato; in the second act the snow storm is accompanied by the wind machine (like the one Richard Strauss used in his Don Quixote). The whole orchestration of the opera was taken as an example by many composers (including another master of orchestration, Maurice Ravel) and as a model to study for the new generations.

Richard Wagner, ca. 1862

The orchestra is perhaps the real turning point: from the idea of opening the opera with a prelude on a closed curtain to the use of the thematic material in a more Wagnerian way, Puccini goes on a deeper level, creating a layer of psychological textures that will dominate the entire opera. The composer himself puts this in plain sight, consciously quoting the famous Tristan chord that opens Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde when Johnson hides at Minnie’s.

Puccini’s score seems to look more at finding the right balance between action and music, using the coup de theatre to increase the involvement of the audience in the story: Johnson’s blood that drips down on Rance’s hands is a great visual element that we are now used to see in another medium that was in its infancy back then, the cinema. With Fanciulla Puccini strives to combine these visual elements with his musical language in a way neither him or his contemporaries had never tried before.

Sources and links:

Puccini’s The Girl of the Golden West by Burton D. Fisher

A special website was dedicated to La Fanciulla del West for its 100 years: fanciulla100.org

A copy of the original play by Belasco is freely available at project Gutemberg

Images: Caruso, Premiere, Film poster, Wagner via Wikimedia Commons

Photos by Andrew Preble and Mike Kotsch

About the author

Gianmaria Griglio

Composer and conductor, Gianmaria Griglio is the co-founder and Artistic Director of ARTax Music.

Interested in some more music? Take a look at this series!