Puccini A to Z – D as in Detractors

I was not aware, though, of how many people nowadays still consider him a B-class composer, with nothing but cheesy melodies accompanied by some, at best, clever orchestration. Or use his music as a comparison in sentences like “a melody cheaper than Puccini’s” as if composing such melodies was something easy. Needless to say, these type of comments make my blood boil: they lack in objectivity reducing one of the highest geniuses of musical history to a good marketing operation, and, ultimately, only championship mediocrity.

Ildebrando Pizzetti

Puccini and his detractors

Aside from the critics who quickly dismissed La bohème and Tosca, the first big shot at Puccini’s music was fired by his fellow composers. Not opera composers, but the ones who created a movement in favor of chamber and symphonic Italian music: Pizzetti, Respighi, Wolf-Ferrari, Pick Mangiagalli, Casella, Malipiero.

The renovation of Italian music

The idea behind the movement was to resurrect the Italian tradition of non-operatic music. How many Italian composers from the 19th century, as a matter of fact, could you name? Paganini, Cherubini, maybe Sgambati or Martucci. But most instrumental composers got buried by opera composers, like Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti and Verdi. And then Giordano, Mascagni, Leoncavallo and Puccini. Opera composers defined the Italian musical landscape for most of the 19th century. The aforementioned movement had its own (good) reasons to be. However, in its iconoclastic fury, the only way to succeed was through the annihilation of the melodramma.

Fausto Torrefranca, a musicologist and critic, fully adopted this strenuous line of defense of instrumental music, identifying Puccini as his main target: in the 1912 assay “Giacomo Puccini e l’opera internazionale” (Puccini and International Opera) he went as far as associating Puccini with homosexuals and Jews, in order to prove that Puccini’s music was the emblem of decadence, having stripped out Italian music of its masculinity.

It does not come as a surprise that this type of approach was largely shared: after all, only a few years later the fascists – who always stressed the importance of the Italian masculinity incarnated in their dux Mussolini – came to power.

The juxtaposition of Puccini with the decadence of Italian art was a theme dear to another group: the futurists. The leader of the movement, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, was no stranger to throw mud at Puccini: in his 1901 review of Tosca – appeared in La revue d’arte dramatique – Marinetti associates the music with the cheapest junk food.

Marinetti pulled no punches, describing the opera as full of “trivial refrains . . . rancid corny old tunes of a fairground, . . . the nauseating stench of candy-floss, of fried food and – above all – the hopeless odor of intellectual scum!”

Tosca, that shabby little shocker

Marinetti, a notorious misogynist, and his followers saw in Puccini’s success the ultimate tribute to the bourgeois, something appealing to the most and therefore worthless. I’m guessing the only thing the futurists and Puccini had in common was the passion for cars and engines…

Torrefranca took it a step further, accusing Puccini of abusing the Italian language. This criticism did not stay confined in the first half of the 20th century, but was passed on through the decades: Joseph Kerman, in his 1956 Opera and Drama, equated lovers of Tosca with fans of “chain-saw” movies.

Puccini’s detractors kept coming for generations: one of the greatest sopranos of all times and an incredible Puccini’s interpreter, Raina Kabaivanska, remembers the presentation of the first production of Madama Butterfly at the Arena of Verona, in 1978. One of the critics attending the press conference dismissed the opera as “sentimental bourgeois, candy-floss in the melody and faded Japanese postcards“.

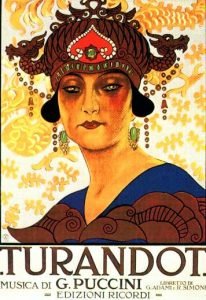

“Turandot is a disgusting opera that is beyond redemption”

Poster of Turandot – 1926

This is the title of an article by Michael Tanner on the Spectator, reviewing the production of Turandot at the Royal Opera House on September 21, 2013. In Mr.Tanner’s eyes, “Turandot is an irredeemable work, a terrible end to a career that had included three indisputable masterpieces and three less evident ones, counting Il Trittico as one” […] and “death prevented him from working it out as painstakingly as he had the rest of the piece — not that it could have saved an opera that is already disgusting” […]”But every Puccini authority raves about its bitonality, the influence of the most avant-garde composers on it, and so forth, as if the surprising harmonies and orchestration could justify this artful rubbish. And for all its dissonances and adventurous sounds, after a few bars anyone would recognize its composer, it’s just that he’s put on a different suit“.

And the fact that a composer has his own fingerprints instead of blending with the masses, making him recognizable right away is a flaw? In what respect?

Mr. Tanner, to his credit, praises Puccini for other works, but here, like many of his predecessors, fails to make a reasonable argument against his music. But then again, I have yet to find a detractor who can provide a credible argument to justify such choice of words. An argument that would possibly go beyond personal taste and be just a little bit more objective.

Fortunately, Puccini never cared much for his critics. He was aiming at the heart of the audience and keeps hitting that target almost a century after his death, despite his past, present and future detractors.

Sources and suggestions:

Ildebrando Pizzetti: picture by Venturini [Public domain]

Puccini without excuses, by William Berger

Vivere senza paura: scritti per Mario Bortolotto, by Jacopo Pellegrini and Guido Zaccagnini

If you want to dig deeper I suggest the following books:

The Puccini problem, by Alexandra Wilson

Giacomo Puccini e il postmoderno, by Renzo Cresti

About the author

Gianmaria Griglio

Composer and conductor, Gianmaria Griglio is the co-founder and Artistic Director of ARTax Music.

Interested in some more music? Take a look at this series!