Barber’s Vanessa: the hopeless yearn for immortal love

The premiere of Samuel Barber’s Vanessa, in 1958, was a grand event. It was Barber’s first opera, yes, but more importantly: it was the first time in over a decade that the Metropolitan Opera House had programmed a first work by an American composer.

Vanessa at the Met

The opening night was a huge success: Barber was greeted as a star by the audience and famous conductor Dimitri Mitropoulos, in charge of the musical direction, was quoted exclaiming: “At last, an American grand opera!”. Barber won the Pulitzer Prize for Vanessa the very same year.

The general enthusiasm did not last long though. Soon enough the opera was flooded with criticisms for its post-romantic language, hinting too much at Puccini and Strauss and therefore not “American” enough. The blind accusations of being too European led one writer to state that “[this opera] is American only in so far as its composer was born in this country.” These type of comments didn’t stay in America: when the opera was presented at the Salzburg Festival, in 1959, the criticisms became even harsher.

Barber eventually revised the opera, in 1964, reducing it from four to three acts, which is the most commonly performed version today. Still, confronted with the critics who found Vanessa un-American, Barber replied:

Art is international, and if an opera is inspired, it needs no boundaries.

Genesis

This is were it gets tricky: in multiple places the main source for Vanessa is attested as Seven Gothic Tales by Isak Dinesen (aka Karen Blixen). However, Giancarlo Menotti, who wrote the libretto, only derived the atmosphere from it. The relationship between Menotti and Barber went back all the way to their time as students: the two had met at the Curtis Institute, in Philadelphia, and built a life-long relationship from there.

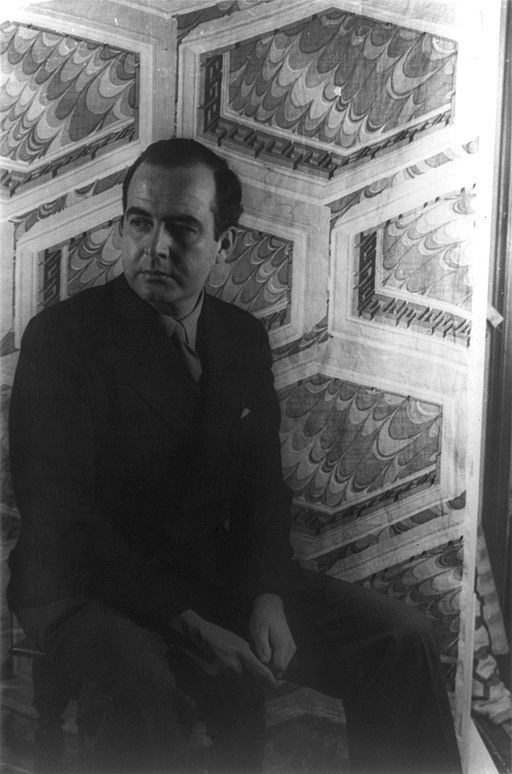

While Menotti approached opera relatively early (a very successful Metropolitan Opera debut of his first opera Amelia goes to the ball dates back to 1938), Barber found his voice at first with songs, chamber music and symphonic works. After winning the Bearns Prize from Columbia University and the prestigious Rome Prize, his fame as a composer was sealed in 1938 with the broadcast of his first Essay for Orchestra, with the NBC Symphony conducted by Arturo Toscanini.

Barber established himself in antithesis with most composers coming back from Europe, who were writing largely atonal music, caught in the net of the 12-tone system. He, however, always remained true to his romantic soul: his music, even when dissonant, oozes lyricism. This was one of the reasons he received a number of commissions: Prayers of Kierkegaard from the Koussevitsky Foundation, the Hermit Songs from the Coolidge Foundation of the Library of Congress, and Knoxville: Summer of 1915, even today one of his most performed pieces.

Barber’s first love affair with opera

The inherent lyricism of Barber’s music convinced the director of the Met, Rudolf Bing, to commission him an opera. In search for a librettist, the composer turned to several prominent writers: Thornton Wilder, Dylan Thomas, Stephen Spender and James Agee. Finding the right match and the right subject turned out to be not so easy. He even flirted, for a while, with the idea of turning A streetcar named Desire into an opera, only to reject it thinking that Tennessee Williams‘ “poetic language is adequate in itself and leaves no room for music“.

Eventually the choice fell on Menotti (or did Menotti volunteer?): he had written the librettos of most of his own operas and Barber felt that nobody could understand the lyric muse from both sides better than him. The collaboration, however, proved to be not so easy: Menotti stopped for an year and a half after writing only the first scene, in order to abide to his own operatic projects.

Poor Anatol – Barber wrote – remained standing in the cold! After the composer threatened to call the whole thing off, Menotti put hands to the project again and finally finished what he had started, producing one of the finest pieces of his career.

The libretto is filled of references: Dinesen’s mirrors recur, covered, in Vanessa’s world. As well as Tennessee Williams’ Blanche DuBois, in Vanessa’s utter inability to look at herself in a glass, fearing the passing of time.

Plot

The subject is a constant juxtaposition of impassioned idealism and carnal reality. Vanessa has secluded herself in her mansion, obsessively waiting for the return of Anatol, a married man with whom she had an affair 20 years previously. She lives with her mother the Baroness and her niece Erika. The latter is the idealistic virginal dreamer; the former, the moral judge, casting her shadow throughout the whole opera, refusing to talk to anyone who, in her mind, would be living a lie: her daughter included, to whom she has not spoken since the breakup with Anatol.

Anatol does make his appearance, but he is not the right one: this Anatol is the son of Vanessa’s old lover and promptly proves his opportunism. After seducing Erika, he turns to Vanessa, having been refused by the young idealist. Anatol is completely incapable of love and Erika, pregnant, demands “each woman’s right to wait for her true love to come“.

Vanessa and Anatol announce their engagement and Erika responds by trying to harms herself in order to abort the baby. Vanessa, in complete denial, leaves with him. Erika locks herself up in the mansion: she will be the one waiting now. Having lied to Vanessa about her pregnancy though, Erika will be facing a future of silence, as, true to her own word, the Baroness stops speaking to her.

Final thoughts

The fact that Vanessa would somehow mirror the thoughts of Barber and Menotti on their relationship is still debatable. According to Menotti himself, Barber claimed that he “felt ours should be an immortal friendship. It is that, but somehow it didn’t turn out the way he imagined it.”

The same thing happens in the opera: both Erika and Vanessa yearn for immortal love, but somehow the end result is not what they expected it to be.

Is it ever?

Sources:

Schirmer, Barber’s only publisher, today Music Sales Classical

A guide to research – Samuel Barber by Wayne C. Wentzel

Samuel Barber: a forgotten neo-romantic great – by Leon McCawley for The Guardian

Samuel Barber: the composer and his music – by Barbara B. Heyman

About the author

Gianmaria Griglio

Composer and conductor, Gianmaria Griglio is the co-founder and Artistic Director of ARTax Music.

Interested in some more music? Take a look at this series!